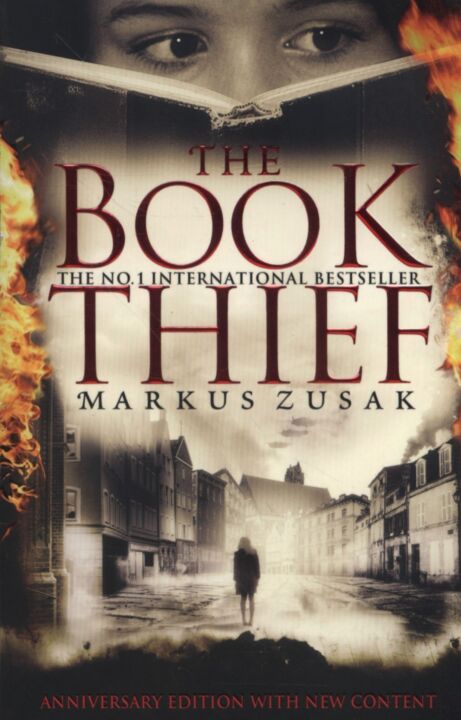

Title: The Book Thief

Author: Markus Zusak

Publisher: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

Genre: Historical Fiction

First Publication: 2005

Language: English

Major Characters: Liesel Meminger, Death, Hans Hubermann, Max Vandenburg, Rudy Steiner, Ilsa Hermann

Setting Place: Fictional town of Molching, Germany, 1939-1943

Narration: First person omniscient, with Death as the narrator

Theme: Death, literacy and power, love and hate in human nature, acts of horror and torment during holocaust

Book Summary: The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

It is 1939. Nazi Germany. The country is holding its breath. Death has never been busier, and will be busier still.

By her brother’s graveside, Liesel’s life is changed when she picks up a single object, partially hidden in the snow. It is The Gravedigger’s Handbook, left behind there by accident, and it is her first act of book thievery. So begins a love affair with books and words, as Liesel, with the help of her accordian-playing foster father, learns to read. Soon she is stealing books from Nazi book-burnings, the mayor’s wife’s library, wherever there are books to be found.

But these are dangerous times. When Liesel’s foster family hides a Jew in their basement, Liesel’s world is both opened up, and closed down.

In superbly crafted writing that burns with intensity, award-winning author Markus Zusak has given us one of the most enduring stories of our time.

Book Review: The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

Having Death as the narrator and having as a central protagonist a young girl in Nazi Germany make The Book Thief by Markus Zusak stand out from the crowd of books about Europe during World War II; this book is good not so much because of the story, but how the author tells it.

In the Book Thief by Markus Zusak, author uses a rich, multi-layered blend of allegory, metaphor and symbolism to create amidst the dirt and depression of Germany during the late 30s and 40s a stark vision of historical and philosophical thoughtfulness. This international best seller features a healthy sense of dramatic irony, with the German setting and the strong use of script-like construction becoming reminiscent, especially the sympathetic depiction of Marxists.

Yes, often, I am reminded of her, and in one of my vast array of pockets, I have kept her story to retell. It is one of the small legion I carry, each one extraordinary in its own right. Each one an attempt – an immense leap of an attempt – to prove to me that you, and your human existence, are worth it.

By using a surreal personification as a narrator, the author has softened the blow of the harsh setting and thus, incredibly, makes the characters more accessible and makes the reader approach an empathy with them that may otherwise be unavailable. I am reminded of Anthony Burgess’ comments about A Clockwork Orange and how he created the Nadsat language not just to add depth to his narration, but also to minimize the brutality of his story. In much the same way, Zusak has used Death as a narrator to ironically assuage the viciousness of the everyday life that Liesel and the Hubermanns experience in their quiet section of Nazi extremism.

“A small but noteworthy note. I’ve seen so many young men over the years who think they’re running at other young men. They are not. They are running at me.” – Death

Death is not just a narrator but also one of the characters. Telling a story from his vantage, about a group of Germans on Himmel (Heaven) Street amidst the moral flagellation of the Third Reich Zusak creates a fecundity of symbolic structure. I found myself getting lost in metaphoric possibilities. What did he mean by that? What could that symbolize? Yet the author does not over generalize or make universal declarations, his approach is far more subtle, and again Brechtian in it’s demystification for dramatic realism; the reader comes to know Liesel Meminger, not as an ultra-real snapshot, nor as a idealized German every girl, but as an actress in a play, knowable and probable, but still a dramatic portrayal.

Through the eyes of Death, Liesel enters from stage left and we follow her through stereotypical misadventures made hackneyed in the World War II genre, but also through the good, the bad, and the ugly that is histrionic enough to be believable and understandable as an expression of real life during Nazi Germany.

“The only thing worse than a boy who hates you: a boy that loves you.”

This is still, though, after all, a representative portrayal of an ugly time. The reader should not look for a Disney moment, there are few. Zusak peppers his chronicle with some scenes of comic relief, but he never lets you forget when and where the action takes place. Expectations of Hollywood commercial breaks will come and go unnoticed on this trip; and all to the credit of its creator, who has crafted that most rare of accomplishments: a commercial success and at the same time an artistic expression.

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak is a very singular literary experience and an enjoyable journey with a young writer from whom we have much to expect.